Art Dudley wrote about the Quad ESL-989 in May 2003 (Vol.26 No.5):Beginning in 1982, the Quad ESL-63 had a fine 15-year run as one of the most recommendable loudspeakers ever, offering as it did a combination of clarity, balance, musicality, and adaptability that few could match. During much of its life, the '63 also sold for a reasonable price compared to anything else that dared call itself "the best," and while it might sound cynical to say so, the cachet of being an electrostatic panel in a world of plain-Jane boxes didn't hurt, either. The ESL-63 was a smash.

But all good things come to an end, and in 1997, when the folks at Quad realized that their flagship was in violation of the tough new CE standards, they pulled the plug—literally: For a short while, traditional boxes were the only speakers Quad made.

Quad the company has changed and changed hands, and for a while things didn't look so hot. But now the firm that started the ball rolling back in 1957 is once again making full-range electrostatics, and, as Larry Greenhill suggested in the November 2002 Stereophile (Vol.25 No.11), this is not just a return but a return to form. I've spent two weeks listening to their new flagship, the ESL-989. I think it's one of the finest loudspeakers you can buy at any price.

The ESL-989 isn't as big a departure from the ESL-63 as the '63 was from its own predecessor, the Quad Electrostatic Loudspeaker. (It was not named the ESL-57, for the same reason that the people who fought in Europe during the years 1914-18 didn't refer to their endeavor as "World War I.") The first Quad loudspeaker was that rarity of rarities: a genuine breakthrough, not just a refinement of something else. Moreover, it sounded wonderful and remains competitive to this day: Some folks think Quad never did better, and when it comes to that model's astonishing clarity and presence, I tend to agree.

But the first Quad had problems: Its crossover sent low frequencies to a pair of bass panels, mid-frequencies to a smaller, central panel, and high frequencies to an even smaller portion of that smaller panel. Because the size of the latter was still fairly big in relation to the wavelengths of the highest sounds it handled, the speaker tended to "beam" high frequencies rather than disperse them widely across the listening area. That wasn't much of a problem at the onset: The first 400 or so Quad Electrostatic Loudspeakers were sold singly, for use in monophonic systems. But with the advent of two-channel stereo, it became apparent that the model's high-frequency beaming made it unsuitable for stereo effects for more than one listener.

Over the next several years Quad's founder and chief designer, Peter Walker, worked up a solution that was itself a near-breakthrough: Instead of sending treble signals to the stators of a treble elecrostatic panel and bass signals to the stators of a bass panel, he sent a full-range signal to a small, circular stator at the center of a comparatively large panel, then sent a time-delayed version of the same signal to a larger circular stator, concentric to the first, and then an even more delayed version of the signal to an even larger concentric stator...and so on, outward across a series of seven rings in all.

This approach offered a number of appealing qualities in one stroke: It created a theoretically ideal spherical waveform, the psychoacoustic effect of which was that music seemed to emanate from a point source well behind the speaker. Because of this, and because the electrical crossover was replaced with a paradoxically more natural dispersion scheme (I say "paradoxically" because it involved channeling the signal through several thousand feet of wire in an inductive delay system), the beaming problems of the ESL were lessened somewhat in the ESL-63. Because the annular/ring approach drove the diaphragm better, deeper bass response was possible. Because the signal was spread across a series of smaller stators, a more consistent reactive load across the frequency spectrum resulted, with the added benefit of greater power handling. And finally, because the audio signal was also attenuated, slightly and incrementally, as it went from the innermost stator to the outermost, transverse wave motion across the single large diaphragm was mitigated, avoiding or at least reducing certain distortions that otherwise plague panel speakers.

The leap in design theory from the ESL-63 to the new ESL-989 is not a huge one. The '989 contains no breakthroughs, and I'm sure no one at Quad would dispute that. On the other hand, while I've never owned '63s, I have had both stock and Crosby-modified samples of them in my home, and I think the ESL-989s are much better speakers. In my room, which is 12.92' wide by 16.67' long by 9' high, the '989 played music with as much tunefulness, drama, and scale as I've ever asked for or heard from other speakers. It also rivaled the best in terms of clarity and low distortion—to me, it sounded even more open and neutral than the '63, and was almost the equal of those truly exceptional original Quads in sheer realism and presence. And not only was its bass extension perfectly satisfying, but, with the exception of the speed of bass fundamentals—which was very slightly lacking compared to the best I've heard—the bass quality of the Quad '989 was astoundingly good. Here, finally, is a Quad speaker with Quad bass.

How did they do it? Well, the ESL-63's diaphragm wasn't a one-piece deal, but rather comprised four panels, stacked top to bottom, each approximately 7" high. The annular ring stators affected the middle two panels only, and the panels above and below them were also driven by a full-range signal—but one that was delayed still further compared to the signal feeding the outermost of the center panels' rings. For the ESL-989, Quad's engineers added two more panels, one at the bottom and the other one at the top. These panels—call them Nos. 1 and 6—are driven by the same signal as panels 2 and 5, with no added delay. The result is bass-wave reinforcement without the intermodulation that would result if you simply made all the panels bigger—and without the drastic price increase associated with a component they're not already tooled up to make. Raising the central stators farther from the floor was probably a good move, too.

The ESL-989 is also built vastly better than its forebears, and I've no doubt these refinements contribute to the new speaker's excellent performance. As LG pointed out in his review, downward-firing louvers in the protective steel grille have been replaced by more sensible straight-through perforations. The grille is also more rigid overall, since it's now formed with a pair of deep vertical creases. The frame is better-built and nicer-looking in every way, and the bottom of the base has threaded inserts that accept adjustable spikes or blunt feet (both included). And I'm told that all the internal wiring has been upgraded—a good thing, considering all those inductors. The only jarring notes, as LG also said, are the '989's cheap binding posts—like dime-store wiper blades on a Lincoln Town Car. But, like those blades, these posts do their job; as someone who believes that massive connectors may degrade rather than improve sonic performance, I would be in no hurry to exchange them for something else. Personally.

Setup

The first thing I noticed when John Atkinson sent me the ESL-989s was their superb cartons and packing material. Maybe this is important only to reviewers and shopkeepers: people who have to unpack and repack audio products many times more often than the average hobbyist, and who often have to contend with cartons that have been around the Horn, shall we say. But someone at Quad thought things through and came up with a box and "modular" Styrofoam packing spacers that can be understood intuitively—and that obviously work well. There are even pictographic unpacking instructions, ;ga la Fahrenheit 451, printed on the outside of the carton. If you need more help than this, you shouldn't be playing with electricity in the first place.

I found it remarkably easy to get a smooth curve and good bass extension with the Quad ESL-989s in my room, and while the former is usually more my goal than the latter when setting up speakers, I'm happy to take whatever I can get.

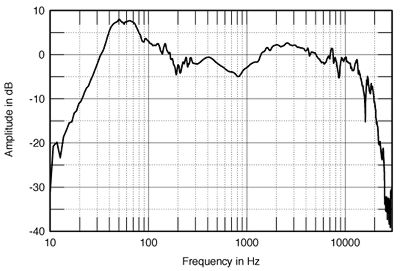

According to my AudioControl SA3050 spectrum analyzer, the ESL-989s were flat in my room down to 31.5Hz, with some useful output at 25Hz. At the other end, their in-room response began a very gentle rolloff at 5kHz, with no useful output above 16kHz. That was with the centers of the speakers exactly 51" from the wall behind them (the short wall), with the outer edges of the speakers exactly 20" from their respective side walls, and with the '989s toed in toward the listening area only slightly. I noted that a more drastic toe-in produced a greater sense of imaging precision for a single, centered (physically and not spiritually, I mean) listener, but doing so sacrificed some smoothness in bass response. A less drastic toe-in also made for less drastic changes in tonal balance depending on where I sat, and even depending on whether I sat or stood: Too much toe-in made things fussier than I care for.

My room isn't acoustically perfect—the standing waves that correspond with its dimensions aren't as evenly spaced from one another as the ideal—but it isn't bad, and the long dimension is capable of supporting low frequencies down to 33Hz, given a speaker capable of muscling them out. The most notable response anomaly I encountered with the Quads—a 4dB notch at 125Hz—was right between the first octave above the standing wave associated with my room's ceiling height (61Hz) and the second octave above the wave associated with my room's length (33Hz). A slighter anomaly, a 2dB dip at 400Hz, seemed less room-related, but in any event I heard nothing in that region that troubled me.

One more mildly tweaky observation before I leave the subject: My AudioControl spectrum analyzer has an adjustment knob that allows me to select the number of decibels represented by each vertical step in the curve, ranging from 1dB to 4dB. My usual approach is to begin with that knob set for 4dB and then move the speakers around until I get a smooth curve—after which I set the knob to a finer gradation, then watch as the curve goes all to hell. I started the same way with the Quads, and, as I said, it wasn't all that hard to get a really smooth, flat curve. Then I switched the step knob from 4dB to 3dB—and watched in utter amazement as the curve remained the same: The '989s were doing even better than I had imagined. For a second, I thought the analyzer was broken.

Listening

The very first time I listened to the ESL-989s, just an hour after plugging them in and turning them on, I was impressed by their smoothness and their convincing and pleasantly distant stereo imaging qualities—all of which is to say that they sounded like Quads. But they didn't really grab or excite me. I thought they were too smooth. Everything I listened to at first sounded as if dipped in a thin coating of something sweet and pleasant, but something that was also keeping me from "feeling" the real texture of what was going on.

My impressions improved drastically over the next day or two. Whether my initial response had been due to the fact that the Quads' diaphragms were not yet fully charged, or to a psychoacoustic thing owing to the fact that I was coming to them from a loudspeaker that is, in fact, very textured—see this issue's "Listening"—I simply don't know. Either explanation seems credible.

The Quads not only sounded good, they could carry a tune—although, lacking hard evidence to back such an observation, I can say only that, after listening several hours a day for the past week, I have yet to be frustrated or bored or put to sleep by the '989s—all of which would have been signs of my having to work too hard to follow or reconstruct musical lines.

I'm a bit less enthusiastic about their rhythmic performance, but only a bit. Listening closely to modern rock recordings where the kick drum has been brought forward in the mix—two that come to mind are The Plimsouls' jangly "A Million Miles Away" (from Everywhere at Once, Geffen GHS 4002) and the wonderful sing-along "Haircut and Attitude," by Manitoba's Wild Kingdom (from ...And You?, MCA 6367)—I heard low fundamentals lagging very slightly, with a mildly rubbery quality compared to the best (or the realest). I did not, however, hear excess sustain or overhang in those notes, and in any event the new Quads were still better than average in this regard.

They also had a bass quality—in terms of the texture and color of the sounds—that I found extraordinary. I used to think that my combination of Lowther horns and Linn Sizmik subwoofer did a fine job of making deep-bass notes that sounded like music. It took the Quad '989s to show me how unduly rosy my view had been. Make no mistake, the Lowther/Linn combo is good, with deep-bass notes that make musical and sonic sense. But the first time I listened to a live recording of an acoustic string band with an upright bass player through the new Quads, I was startled: Here, finally, was the cliché come true—of midrange and deep bass that sounded as if cut from the same cloth.

Forgive the obvious, but I also tried Bach's Toccata and Fugue in D Minor (Lionel Rogg's, on EMI), and that low D was impressive, to say the least. More obviousness followed when I spent time with Gilbert Kaplan's fine recording of Mahler's Symphony 2 (MCA Classics MCAD2-11011)—always a pleasure, in any event, for both its musically sensitive approach, the high performance caliber, and the handy indexing of various themes and passages. The '989s did an amazing job with that low C in the double basses in the opening bars, with believable weight and just the right decay: If you've heard them live and close up in this piece, you know that this is how they're supposed to sound and feel. (Of course, the Quads were also good enough to let me hear how fuzzy—not raspy or harsh, just slightly fuzzy—this 1987 PCM recording is.)

I'd never before heard this combination of pitch accuracy, color, and sheer impact in the drums in the Schnell passage of the first movement. (See? Those indexes allow even me to sound smart about this piece.) Ditto the third movement's beginning (In ruhig fliessender Bewegung) and ending (the "scream of anguish"), played so loud I thought my pants were going to fall apart. Likewise the "scream's" repetition at the beginning of the fifth movement.

Throughout, there was no hint of strain or distress—let alone any suggestion of the Quads' self-protection system shutting them down. Granted, I probably don't listen to music played back as loudly as a lot of other people enjoy: Loud music makes me cranky, especially music played in the home louder than it would be live. (That, next to an intense dislike of air travel, is why I avoid Consumer Electronics Shows.) Still, I've had these speakers playing extremely loudly at times, with no trouble. I assume that, in contrast with the difficulties Larry Greenhill experienced in this regard, the smaller volume of my listening room was a boon.

Conclusions

Anyone thinking of spending $8000 on a pair of speakers—reasonable though I think that is in the context of other perfectionist components—has a right to wonder whether they'll play loudly enough, or reproduce the bottom octave well enough, or whatever. Those elements of hi-fi loudspeaker performance are important to me, too.

But let's not lose sight of the real goal: Playing back your records in a way that draws you in and keeps you engaged with your favorite music—consistently, no matter what. In that sense, the Quad ESL-989s reign. My music-loving wife enjoyed them every bit as much as I did, and spoke often of looking forward to playing records through them at the end of the day. "This is what speakers should sound like," she said. I couldn't disagree.

Of course, you shouldn't just buy them willy-nilly. Something like the Quads must be heard first, ideally in your home. Room volume will certainly affect their performance, both in the ways described above and in the sense that the volume of air in your room will act as an integral part of the diaphragms' suspension, just as the volume of air inside an acoustic-suspension loudspeaker helps control the bass driver: Change that and you'll change the sound in many ways.

Also—like it or not—this is one instance where amplifier power is best served in American-size portions. While my beloved 300B amp sounded lovely playing small-scale music on the '989s at very soft levels, that's hardly an everyday solution. I'm just talking through my hat here, but I'd doubt if even the great Audio Note P2SE—the 17W amp that sounds so good on the original Quad Electrostatic Loudspeaker—would cut it with these new ones in most settings. Think 30 or 40W minimum, more being better, up to a point.

If the original Quad was the audio equivalent of an E-type Jag, then the ESL-989 is their modern XKR coupe—Brembo brakes, dynamic stability control, six-speed tranny, and all. The relatively Spartan cachet of the original is a thing of the past, and the company that made it has changed forever—but the new model is better in almost every way, not to mention one of the best you can buy, period. I generally keep my nose out of other people's business, especially when that business is hi-fi retailing: Nevertheless, I would not want to be in the position of someone who is trying to sell an $8000/pair low-efficiency speaker that isn't these.

Peter Walker, amateur flutist and the inventor of the ESL-989's predecessors, turns 87 this year, and although he's no longer involved with the firm, I'm told he continues to stay in touch with senior members of the modern Quad company's service staff. Many happy returns to the man whose ideas have made home music so much better.—Art Dudley

Similarly, Quad's ESL-989 electrostatic loudspeaker caught my visual attention before I ever heard them. I was already strongly attracted to the speaker for its unique place in the history of high-end audio. Just as Prague's historical richness enhanced the classical-music performances I heard, the Quad ESL's unique reputation was appealing on its own.

Similarly, Quad's ESL-989 electrostatic loudspeaker caught my visual attention before I ever heard them. I was already strongly attracted to the speaker for its unique place in the history of high-end audio. Just as Prague's historical richness enhanced the classical-music performances I heard, the Quad ESL's unique reputation was appealing on its own.