Infinity Modulus loudspeaker & Modulus subwoofer

John Atkinson, November, 1990

![]()

As much as I'm tempted by the impressive sweep and scale with which some of the large, full-range loudspeakers endow music, for some reason I find myself more at home with more compact examples of the breed. This is not through lack of familiarity with large speakers, a pair of B&W Matrix 801s occupying pride of place in our living room (which also serves as my wife's listening room). Yet I find myself hankering after that ultimate soundstage precision that only minimonitors seem capable of producing: the loudspeakers totally disappearing, vocal and instrumental images hanging in space, truly solid—the prefix "stereo-" is derived from the Greek word stereos, which means solid—so that a rectangular, totally transparent window into the concert hall opens at the rear of your room. In addition, the necessarily limited low-frequency extension offered by small speakers makes it much easier to get the optimum integration with the room acoustics below 100Hz.

If only the loudspeakers that were the champs at that didn't at best reproduce instrumental sounds in such Munchkinesque a fashion or, at worst, present them with all the weight and life sucked out of them. Hence my quest to find a small, high-performance loudspeaker which nevertheless presents musical sound in a sufficiently natural manner that you are not continually reminded of the speaker's lack of ultimate bass extension. I eagerly await delivery of a pair of Wilson WATT IIs; in the last five years or so, the only small speakers that have gone some way toward meeting my criteria are the Celestion SL600Si and SL700, the Rogers LS3/5a, and the Acoustic Energy AE1, with the Spica TC-50 an honorable runner-up (footnote 1). All are excellent but very different examples of the genus minimonitorus, with very different balances between strengths and weaknesses. But if I had to choose just one small speaker to listen to for the next 10 years, any one of those would suffice.

But I'm still on the lookout for that ultimate minimonitor, the speaker that apart from having a lightweight low register would give away nothing to the very best full-range speakers. Which brings us neatly to the subjects of this review. Infinity's Modulus is an example of the direction taken by designers of high-performance minimonitors: extensive use of high technology to max out on a small speaker's intrinsic merit.

Infinity Modulus

Although it was first shown at the 1989 Chicago CES, the tiny Modulus didn't go into full production until earlier this year. Although it can be used in its own right, it is recommended for use as the basis for a full-range system when allied to Infinity's Modulus Subwoofer. Matching floor stands and wall-supports are available; the entire system has obviously been extremely well thought-out in terms of integration and ease of setup.

The Modulus Satellite looks immaculate, being finished on all surfaces except the front in glossy black or white polyester resin. The sealed cabinet is constructed from, to quote from Infinity's literature, "extremely stiff, ultra-high-density multi-fiber panels laminated to an acoustically absorptive, visco-elastic substrate." After reading that, you can probably understand that the very first thing I did was to subject the cabinet to the knuckle-rap test. Well, the Modulus cabinet is dead. All I got for my pains were sore knuckles. As well as the damping pads attached to the cabinet's interior walls, a horizontal brace locks the front, back, and sidewalls together just above the woofer, and the interior is filled with acoustic wadding.

The sculpted-looking front baffle is molded in structural foam and sports two drivers on its stepped profile. The woofer features a tiny (3.25" diameter) curvilinear cone, injection-molded from polypropylene loaded with graphite fibers to give a high stiffness/mass ratio, and is constructed on a diecast aluminum basket. The half-roll surround is butyl rubber to damp standing waves within the cone, and the unit is intended to handle frequencies up to 4kHz. The tweeter is the EMIT-k as used in the IRS Beta and IRS V loudspeaker systems. This is a ribbon unit where a voice-coil is etched on a Kapton substrate and freely suspended between the poles of powerful neodymium magnets.

Unlike the more expensive IRS loudspeakers which use, I believe, first-order crossovers, the Modulus marries the outputs of its two drivers with a fourth-order type. This is constructed on a small printed circuit board attached to the rear of the two pairs of binding posts. Component quality is high, the capacitors (apart from one electrolytic) being SiderealKaps and the inductors ferrite-cored. The cables from the crossover to the drive-units are terminated with push-on tags, however, rather than with solder joints. The binding posts are supplied with the two positive and two negative posts strapped with sturdy, gold-plated bars. These can easily be removed to allow bi-wiring or bi-amping. Above the terminal posts is a coin-slot–operated tweeter-level control.

Both drive-units are fixed in place with four Allen-head bolts. It's always a good idea to check the tightness of drive-unit mounting bolts, as I've known them to work loose in shipping. Everything was secure with the Infinity Modulus, however; a good sign.

It might be thought that the part of the stepped baffle immediately beneath the tweeter might interfere with its sound. The ribbon, however, being significantly longer than it is wide, will have limited vertical dispersion in the frequency region it is asked to handle, and won't "see" the obstruction. This won't necessarily be true for the grille and its frame, however, and Infinity's engineers have to gone to considerable trouble to render this acoustically transparent. Black material is stretched over a minimal space-frame molded from what appears to be polystyrene. When in position, the grille completes the rectangular appearance of the loudspeaker.

The Modulus subwoofer is an almost cubical unit finished in the same high-gloss finish as the satellites and resting on four "Iso-tip" conical feet. A single 12" drive-unit, fitted with an IMG cone and driven by an integral 250W amplifier, adorns one face, this normally being covered by a black cloth grille. One of the unit's vertical corners consists of the vertically ribbed heatsink fins for the power amplifier; these got hot only under sustained drive with music having a large amount of sub-100Hz information—okay, organ music!

As with Infinity's IRS subwoofers, the Modulus drive-unit is servo-controlled, both to minimize distortion and to flatten and extend the system's response below its natural resonance. The woofer's drive signal is supplied to the unit via a long cable fitted with 5-pin DIN plugs on both ends. One plug fits into the base of the subwoofer next to its on/off switch, the other into the control unit, which can be sited near the system preamplifier. The control unit takes the stereo outputs from the preamp, passively high-pass–filters them with an array of 0.22µF series capacitors—the exact number of capacitors in circuit depends on the power amplifier's input impedance—and sends the equalized signals to the power amplifiers used to drive the satellites.

It also combines the channels, low-pass–filters the resultant mono signal, and sends that signal to the subwoofer. The high-pass capacitor configuration is adjusted by means of two DIP-switch arrays on the rear panel; the low-pass crossover frequency, subwoofer level, and phase (continuously variable from 0° to 180°) are adjusted with front-panel rotary knobs. A switch allows the user to choose between extension to 22Hz (–3dB) or 35Hz, the latter being useful in problem rooms or with sources having excessive rumble. When the subwoofer is on but the control unit off, the unit goes into standby mode, this indicated by a red LED under the grille lighting.

Footnote 1: Which I reviewed in Vol.12 No.5, Vol.11 No.9, Vol.12 Nos.2 & 3, Vol.11 No.9, and Vol.12 No.10, respectively.

Both satellites and subwoofer come with comprehensive Owner's Manuals covering all aspects of setup and use and offering good advice on where to site the units within the room to get the optimum sound. Would that all loudspeakers were as well served in this respect.

The sound

The Modulus pedestals were supplied ready-assembled; all that I needed to do was to fill the 22", diecast aluminum center pillars first with 12 lbs of No.8 hard lead shot, then with dry sand to within 1" of the top plate. A foam plastic insert then ensures that the top plate is adequately damped. The base of the Modulus pedestal is fitted with four carpet-piercing spikes. These can be adjusted from above to ensure the stand is free from rocking; knurled screwtops then lock them in place. For those who are leery of spikes, Infinity supplies spike covers. The Modulus speaker is supplied with three conical "Iso-tip" feet, which mate with rubber-lined sockets on the top of the pedestal. Contrary to British audiophile practice, there is therefore some compliance introduced between the speaker and stand. Two knurled screws secure the speaker to the pedestal top-plate; these are not intended to be fastened tight, only to prevent the speaker from being carelessly knocked to the floor. Following Infinity's instructions, I tightened the mounting screws all the way, then backed off a full turn.

As mentioned above, Infinity apparently spent a lot of design attention on the Modulus's grille. Auditioning the speakers with and without grilles, however, left me in no doubt that the smoothest treble and the best imaging was obtained with the Modulus used au naturel. This was how I continued with the auditioning, therefore.

Although it is not mentioned in the Owner's Manual, I understand the Modulus does need fairly rigorous break-in before reaching its optimum performance. Accordingly, I drove the review pair with pink noise at quite a high level overnight for two nights before attempting any serious listening (footnote 2). I started off with the speakers toed-in to the listening seat, but found that pointing them straight ahead minimized a slight degree of liveliness in the low treble. I also started off with the speakers 6' away from the side walls and some 4' out into the listening room, but reduced this latter distance to 30" to usefully add a bit of midbass reinforcement.

The Moduluses are quite definitely minimonitors when it comes to the bass registers, 63Hz being about the subjective limit. Bass instrumental fundamentals were absent and the well-damped nature of the speaker's upper bass meant that the sounds of wide-ranging instruments like the piano sounded too small for ultimate satisfaction. The double bass also suffered to a greater extent than, for example, with the similarly sized LS3/5as. At the start of the Adagietto of Mahler's Symphony 5 (VPO/Bernstein, DG 423 608-2), the double basses punctuate the accompanying harp arpeggios with soft pizzicato fundamentals to reinforce the harmonic movement, only switching to their bows for a dominant pedal when the strings plunge down before the theme's first cadential resolution—a goosebump moment on speakers that have any significant output in the middle bass. Via the Moduluses without the subwoofer, the relative absence of the harmonic underpinnings left the music sounding rather thin. It wasn't that the double basses weren't there, but that they were just too lightweight to be effective. Via the Rogers (which is certainly more colored overall than the Infinity speaker), the upper bass was just sufficiently exaggerated to fool the ear in this respect.

The Moduluses did many other things well, however. They are impressively neutral in overall balance, being ostensibly flat-sounding from the upper bass to the high treble. The top octave can sound a little over-emphasized, exaggerating the audibility of tape hiss and LP surface noise, but the tweeter-level control offers sufficient range to compensate for this. Instrumental tone colors were therefore reproduced with an excellent degree of faithfulness, something I had not experienced to anything like the same degree with prior Infinity models.

Coloration levels were also very low; the only traces of character noticeable, and then not with every kind of music, were a slight "cupped-hands" color to male spoken voice, which also gave recorded flute too warm a sound in its lower registers, and some liveliness in the lower treble which was most noticeable on piano.

As with other very small-baffled loudspeakers, lateral image precision was stunningly precise. Images were locked into position, giving an excellent sense of solidity to the sound. Something I found surprising, however, was that image depth was more restricted than I'm used to with other good loudspeakers. The depth of image test on the Chesky Test CD, for example, has Bob Angus speaking and David Chesky playing a tambourine recorded increasingly farther from the microphone. On many speakers, the direct sounds become swamped with reverberation as the sources get quieter due to being farther back. Via the Moduluses, that reverberation seemed somewhat suppressed, so that the sounds tended to remain dry even as they got quieter. The same thing was noticeable on both my piano recording and Robert Harley's acoustic guitar and double bass recording on the Stereophile Test CD, both of which should produce instrumental images set back a little behind the plane of the speakers with a good sense of the surrounding acoustic apparent. The Infinities noticeably reduced the depth of image, even though the instrumental sounds were both well-located laterally and very natural-sounding.

Though the lack of mid- and low bass will be a factor here, my experience of other loudspeakers suggests that this subjective effect could also be due to a lack of energy in the presence region, which can have the effect of suppressing reverberant information. That this might be a problem with the Modulus was reinforced by the speaker's dynamics, which were on the polite side. Despite their diminutive dimensions, the Infinities would play quite loud, capable of giving spls around 96dB in my room before too much of a sense of strain cut in in the low treble. However, there was a certain lack of excitement about the sound even at highish levels, as though the speakers were unwilling to "give," in musical terms. Partly this was associated with a slight degree of congestion in the lower midrange which cut in with increasing level—this congestion was more severe before the speakers were broken-in—but it was also due to a reticence in the speaker's presence region. Even such well-recorded rock music as John Hiatt's Bring the Family (A&M SP-5158) lacked impact, even from LP, which was generally served better than CD in this respect by the Moduluses. Hiatt's acoustic guitar sounded as though it had been strung with a heavier gauge of string, reducing the transient attack of the instrument.

The only kind of music to satisfactorily avoid this over-polite rendition was rock, and then only when it was over the top, excitement-wise, in the first place. The opening track on Luka Bloom's excellent Riverside CD (Reprise 9 26092-2), "Delirious," features frantic Ovation acoustic guitar strumming—an unmistakably "rubber-bandy" tone color—behind his voice. No problems via the Moduli—goosebumps at last!

Subwoofing

Following the auditioning of the Moduli on their own , I hooked up the Modulus subwoofer and its control unit. At first, the output of the Mark Levinson No.26 fed the Infinity control unit, with then the high-pass outputs feeding the Mark Levinson No.20.5s via 15' lengths of Audio Research cable. The DIP switches on the controller's rear were adjusted to suit the Levinson's 50k input impedance, which gave a measured response 6dB down at 100Hz. The subwoofer was positioned midway between the satellites, at first adjacent to the rear wall, then some 2' away from it. Unfortunately, no matter what combination of signal and component grounding I tried, I couldn't rid the system of hum through the satellites, presumably due to a ground loop of some kind. (The hum never came from the subwoofer.) Floating the CD player with cheater plugs, or the preamp, or one or two power amplifiers, or the Infinity subwoofer, or any combination of the above resulted in no change in the hum level, though floating all the components gave a large increase in the hum level. I also tried reversing the polarity of the floating components with no effect.

Finally, I fed the variable output of the Meridian 208 straight into the Infinity controller; this gave a slightly lower level of hum, as did making the only system ground that of the subwoofer. The only way to eliminate the hum was to take the satellite feeds from the crossover's parallel set of inputs. These are unfiltered, however, so much of the dynamic advantage offered by subwoofing was lost.

Footnote 2: Sometimes the obvious never does strike you. It was Tom Norton who pointed out to me that the least aurally fatiguing way in which to break-in speakers is to wire the pair in inverse polarity and place them face-to-face. This way, most of the midrange and bass energy cancels, minimizing the overall level of sound but still allowing you to work the speakers hard.

To put this problem into perspective, the spl of the hum measured about 56dB unweighted at the listening position, lower than the background noise on the Dorian Pictures recording, but in the very quiet listening conditions I have available, any level of hum is audible except when masked by the music. I assumed that either my controller or subwoofer were faulty or needed an internal modification. I therefore ignored the background hum for the purposes of this review. If you are interested in the full-range Infinity Modulus system, however, it would be worth checking that you do not get any hum when the speakers, subwoofer, and controller are hooked up with the rest of your system before you make the final purchase decision.

Setting the control unit's settings to give good integration between the subwoofer and the satellites was rendered reasonably straightforward by the range of adjustment possible. For those without a spectrum analyzer, the 1/3-octave warble tones on the Stereophile Test CD, which range from 200Hz to 20Hz, make it possible to get good integration by ear. I actually did it this way, then used the spectrum analyzer to fine-tune the setup. Interestingly, doing it by ear gave a subwoofer setting that turned out to be about 4dB too sensitive when measured. At first this sounded "impressive" with music, but then became wearisome to the ear.

For fine-tuning of the subwoofer settings, recorded harp and piano seemed to be the most sensitive instruments with which to judge the subwoofer level, their lower strings easily sounding tubby with even slightly too much subwoofer level or too high a low-pass setting. The most sensitive adjustment was the woofer's low-pass frequency. Setting it to be the same as the nominal 140Hz high-pass feed to the satellites tended to give too much energy in the room between 100Hz and 200Hz. I ultimately settled on 90Hz or so, but this was music-dependent, the optimum setting for orchestral music or for organ being too high for piano.

Once set up optimally, the Modulus subwoofer did indeed turn the Modulus satellites—facing straight ahead, moved some 4' out into the room, and driven by the Audio Research Classic 60—into a full-range system, with low bass that could be felt to pressurize the listening room with appropriate recordings. The Dorian organ transcription of Pictures at an Exhibition (DOR-90117) was a natural CD to reach for. Track 2, "Gnomus," has some deep organ "barks" underlying the gentle melodies. The Modulus system reproduced these with an excellent sense of dynamics, even at very high levels, the low bass interjections remaining clean without any sense of their interfering with the higher-frequency information. There was also a much better sense of reproduced space than with the satellites on their own.

This better sense of space was also found with recordings that didn't contain much fundamental energy below 40Hz. The Chesky re-release of Brahms's Piano Concerto 2, with Gina Bachauer and the LSO under Dorati (Chesky CD36), for example, has a warm orchestral sound on the satellites, but sounds a little closed-in. Adding the subwoofer opened up both the sound and the soundstage, allowing the performance to communicate more directly. The cello solo in the third movement, in particular, could be heard to "breathe" with the music's flow more effectively, diminishing the effect of its slightly dry presentation compared with both the other strings and the piano, the latter having a more ambient bloom around its image.

How about other kinds of music? In the past, while appreciating the weight and authority lent classical orchestral music by a subwoofer, I have found the effect on rock has been ultimately disappointing due to the subwoofer's sluggish output failing to integrate with the faster upper bass of the satellites. Imagine someone banging four-to-the-bar on a second bass drum with a soft felt-tipped beater to visualize the subjective effect. Being fortysomething, it was time, therefore, to reach for Led Zeppelin, specifically "Dazed and Confused" from the first album, released on CD as Atlantic SD 19126-2. The Infinity passed this severe test with flying colors, once the subwoofer level had been backed off a little. (One of the problems with any subwoofer is that the optimum match between it and the satellites does vary slightly from track to track.) The sound was seamless, and overwhelming. Boy, that John Bonham could dish up the thunder when required! Imagine the effect on visitors when you cover up the subwoofer and let them think it is just the Moduluses producing this cataclysmic sound.

Levels at the listening seat could reach about 100dB at the listening chair with the Audio Research Classic 60, about 4dB higher with the Mark Levinson No.20.5s, before a sense of strain in the lower treble had you reaching for the volume control. I'm sure the subwoofer would go considerably higher in level, enabling its use with more sensitive satellites.

The final track to go on the Linn with the complete Modulus system was a request from Larry Archibald, "Die Tänzerin" from Ulla Meinecke's 1983 album on German RCA (PL70932). This sparsely mixed track features Fraulein Meinecke's macho-mocha-toned voice accompanied by fingerpopping, an electronic drum machine, and a funky synthetic piano sound, all of which are bathed in artificial reverberation. It used to be a favorite test of mine to count the discrete echoes of her voice; with indifferent gear, particularly amplifiers, you would at best get just three echoes; with good amplification and speakers, they would last all the way until the next voice entry (and you know they were still echoing on under the voice). This track perhaps produced the most satisfyingly musical sound I heard from the full-range Modulus system. The voice was natural, palpable, the electric piano boogied with its full quota of weight—I would have said "majesty," but that attribute is not intrinsic to electric piano sound—and the reverberation extended from the tip of my nose to infinity. This is about the closest I have heard in my room to good live rock sound!

Conclusion

To say that I was impressed with the appearance of the Modulus system and the thoroughness with which its designers have arranged for its optimum setup is an understatement. The appearance and quality of fit'n'finish render satellites and subwoofer products that to see is to want to own. This is an often overlooked part of high-end design, but it is one, as Arnis Balgalvis has pointed out in these pages, that can be no less important than ultimate sound quality. To own products as superbly and desirably styled as these is a gratifying experience.

But sound quality is what Stereophile's reviewers are supposed to give the highest priority in their value judgments, and here the Modulus satellites on their own just fail to get a recommendation. Certainly, the Modulus satellite is the most neutrally balanced Infinity speaker I have heard in familiar surroundings, offering a basically flat frequency response within its low-frequency bandwidth limitation, apart from a slight amount of top-octave emphasis which can be somewhat ameliorated with the HF control. With the exception of the slightly congested lower-midrange and the slight liveliness in the lower treble, the Moduluses also feature gratifyingly low levels of coloration, and can throw a well-defined stereo image. During my entire auditioning, however, with both Audio Research and Mark Levinson amplifiers there was a noticeable politeness to the speakers' presentation of music, a blandness if you will, that detracted from the musical values of the recordings I played.

Please don't get me wrong. I am not saying that the Modulus by itself is bad. Its performance is in many ways excellent. But, to rather more of an extent with CD than with LP, the sound consistently failed to raise goosebumps. Couple that with its necessarily limited low-frequency extension and consider that the Modulus is not inexpensive at $1300/pair including the excellent pedestals, and I hope you can see where my verdict is coming from. The competition at this price point is intense, with superb-sounding models offering good bass performance from Vandersteen, Thiel, Spica, and Acoustat to contend with.

When the satellites are coupled with the Modulus subwoofer, things take a somewhat different turn. Relieved of the responsibility for handling nearly all the bass frequencies, the Modulus satellite's lower midrange eases up considerably. The lack of clarity noted above doesn't entirely disappear, but is reduced to a level that is only occasionally noticeable. The entire treble region seems more neutral with an extra two and a half octaves of bass extension to balance against. There is still strong competition at or below the $3300 price point—the Mirage M3 comes to mind, for example, as does the new Magnepan MG3.3, not to mention the Thiel CS3.5—but the Infinity Modulus full-range system scores in offering true flat extension almost to 20Hz, within its loudness limits of 100dB or so in a reasonably sized room, coupled with a fundamentally neutral balance.

Though its overall presentation is still on the polite side of things, I derived considerable musical enjoyment from the complete Modulus system, particularly from LP, where the overall performance would merit a Class B recommendation in Stereophile's "Recommended Components."

On its own, the Modulus subwoofer is one of the better units I have experienced, presumably due to its servo-controlled nature. When optimally set up, it didn't detract from the satellite speakers' performance by adding the ill-defined grumble that can be so typical of subwoofer sound. Its controller offers the user considerable flexibility in optimizing the sonic match with the satellites—it worked superbly with the Monitor Audio Studio 10s, for example—and, assuming the hum problem was either specific to my system or due to a manufacturing fault, I can confidently recommend it to those who love the sound of their minimonitors, and therefore wouldn't countenance replacing them with full-range speakers, but who want just a little more of those seductive low frequencies.

Sidebar 1: Specifications

Infinity Modulus: two-way, sealed-box, stand-mounted loudspeaker. Drive-units: 2.125" by 0.5" EMIT-k ribbon tweeter, 5.5" (140mm) IMG (Injection-Molded Graphite) cone woofer. Crossover frequency: 4kHz. Crossover slopes: 4th-order, 24dB/octave, Linkwitz-Reilly. Frequency response: 80Hz–45kHz ±2dB. Sensitivity: 84dB/W/m (2.83V). Nominal impedance: 5 ohms. Amplifier requirements: 50–200W.

Dimensions: 12" (305mm) H by 7" (178mm) W by 10.625" (270mm) D. Weight: 12 lbs (5.5kg) each.

Finishes available: gloss black and white.

Price: $1000/pair (matching stands cost $300/pair; matching wall brackets cost $129/pair), 1990; no longer available (2006).

Infinity Modulus Subwoofer: sealed-box, servo-controlled subwoofer with integral 250W amplifier and separate control unit. Drive-units: 12" IMG (Injection-Molded Graphite) cone woofer. Crossover frequency: 140Hz, high-pass; adjustable from 40Hz to 210Hz, low-pass. Crossover slopes: 1st-order, high-pass, 6dB/octave; second-order, low-pass, 12dB/octave. Bass extension (–3dB): selectable, 22Hz or 35Hz.

Dimensions: 19" (483mm) H by 17.5" (444.5mm) W by 17.5" (444.5mm) D, subwoofer; 7.25" (184mm) by W 2" (51mm) H by 5" (127mm) D, control unit. Weight: approximately 75 lbs (34kg), subwoofer.

Price: $2000 each (1990); no longer available (2006).

Common to both

Approximate number of dealers: 120.

Manufacturer: Infinity Systems Inc., Chatsworth, CA (1990); Infinity Systems, 250 Crossways Park Drive, Woodbury, NY 11797 (2006). Tel: (800) 553-3332. Web: wwww.infinitysystems.com.

Sidebar 2: Review context

The speakers were positioned for the best sound (with only one pair of loudspeakers in the 21' by 16' by 9' listening room at a time), some 4' from the longer rear wall (which is faced with books and LPs) and approximately 5' from the shorter side walls (which also have bookshelves covering some of their surfaces). Source components consisted of a Revox A77 to play my own and others' 15ips master tapes, a Linn Sondek/Ekos/Troika setup sitting on an ArchiDee table to play LPs, and Kinergetics KCD-40 and Meridian 208 (Bitstream) CD players. (The latter also saw some service as the system preamplifier.) Amplification consisted of a Mod Squad Phono Drive EPS and a Mark Levinson No.26 line-level preamplifier driving either an Audio Research Classic 60 or a pair of Mark Levinson No.20.5 monoblocks via 15' lengths of Audio Research unbalanced interconnect or AudioQuest LiveWire Lapis balanced interconnect, respectively. Speaker cable was 5' lengths of AudioQuest Clear Hyperlitz, doubled-up for biwiring.—John Atkinson

Sidebar 3: Measurements

I use a mixture of nearfield, in-room, and quasi-anechoic FFT measurement techniques (using primarily DRA Labs' MLSSA system with a B&K 4006 microphone, but also an Audio Control Industrial SA-3050A 1/3-octave spectrum analyzer with its calibrated microphone) to investigate objective factors that might explain the sound heard. The speakers' nearfield low-frequency responses and impedance phase and amplitude were measured using the magazine's Audio Precision System One.

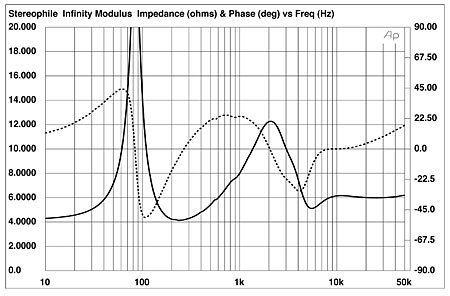

There are no surprises in the Infinity's measured impedance (fig.1). The sealed-box tuning and the lightweight balance are shown by the peak in the bass, reaching a maximum of 26.8 ohms at 84Hz, while the peak centered on 2kHz is due to the crossover. Although its impedance drops to between 4 and 5 ohms in the low bass and lower midrange, the Modulus shouldn't be too hard a load for a good amplifier to drive, particularly as, in common with nearly every speaker I've ever measured, the maximum phase angle does not occur when the magnitude is at a minimum. Above 8kHz, the tweeter presents pretty much a 6 ohm resistive load with its control set to 12 o'clock. The Modulus's estimated sensitivity was around 85dB/W/m at 1kHz.

Fig.1 Infinity Modulus, electrical impedance (solid) and phase (dashed) with treble control at 12:00 (2 ohms/vertical div.)

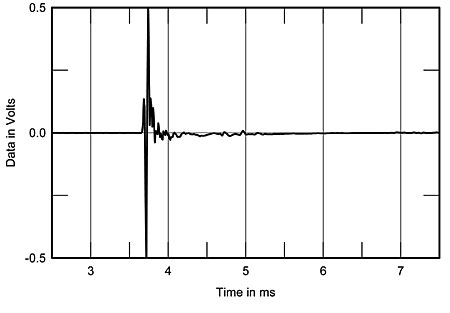

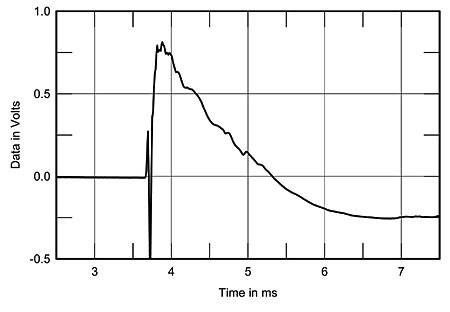

The Modulus's impulse response 48" away (footnote 1) on the HF axis is shown in fig.2 and the step response in fig.3. (The grille was left off for these and all the other measurements, except where noted.) Again, there are no surprises, though I would have expected slightly more overhang from the high-order crossover.

Fig.2 Infinity Modulus, impulse response on tweeter axis at 48". (5ms time window, 30kHz bandwidth.)

Fig.3 Infinity Modulus, step response on tweeter axis at 48". (5ms time window, 30kHz bandwidth.)

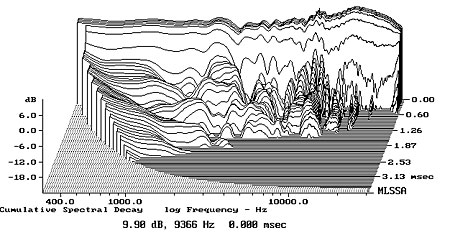

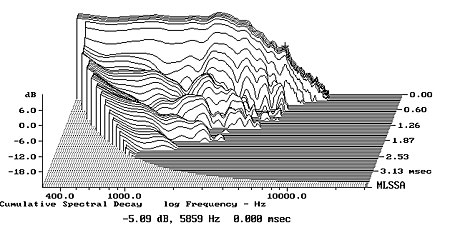

Fig.4 shows how the speaker's frequency response changes as that impulse decays: pretty clean, the "waterfall" is only marred by two slight areas of hash, around 2kHz and between 5kHz and 10kHz, which might correlate with the slightly bright treble character noted during the auditioning. The "crinkly" appearance of the latter region seems to be typical of planar drive-units, though what it represents I'm not sure. The step responses of the individual units show that they're connected with the same polarity, and the effectiveness of the stepped baffle is shown by the fact that the output from both units is coincident in time on the tweeter axis. The woofer seems very clean toward the top of its passband, as can be seen from its waterfall plot (fig.5), though again a mild mode is visible at 2kHz or so, this possibly tying in with the treble congestion heard at high levels.

Fig.4 Infinity Modulus, cumulative spectral-decay plot at 48" (0.15ms risetime).

Fig.5 Infinity Modulus woofer only, cumulative spectral-decay plot at 48" (0.15ms risetime).

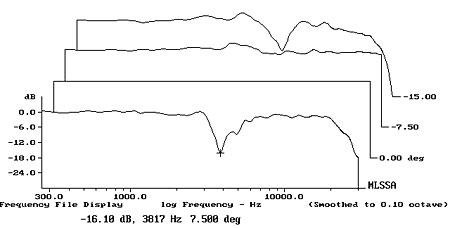

Fig.6 shows the anechoic response of the two drive-units on the tweeter axis at a distance of 48" with the tweeter control set to 12 o'clock (as it was for all these measurements). Note the steep acoustic rollout of the tweeter below 3kHz, as well as its rising response in the top octave and a half. Looking at how the drivers' outputs integrate, fig.7 shows the anechoic response of the Modulus from front to back, 7.5° below the woofer, on the woofer axis, on the tweeter axis, and 7.5° above the tweeter, all, again, at a distance of 48". The responses in front of the loudspeaker are equally smooth, but those above and below the Modulus feature a significant notch at crossover. The vertical listening window will therefore be reasonably critical, and it is possible that the room reverberant field may also lack energy in the presence region.

Fig.6 Infinity Modulus, acoustic crossover on tweeter axis at 48", with nearfield woofer response shown below 300Hz.

Fig.7 Infinity Modulus, vertical response family at 48", normalized to response on tweeter axis, from back to front: difference in response 7.5° above axis, reference response, differences in response 7.5–15° below axis.

I looked at the effect of the grille by repeating the HF-axis response in fig.7 with it on. Although the resultant response is not shown, the grille appeared to reinforce the depth of the on-axis crossover suckout, something that I had suspected from my auditioning. The tweeter-level control increases or reduces the drive-unit's output by +2 or –2dB above 5kHz compared with the level with it set to 12 o'clock.

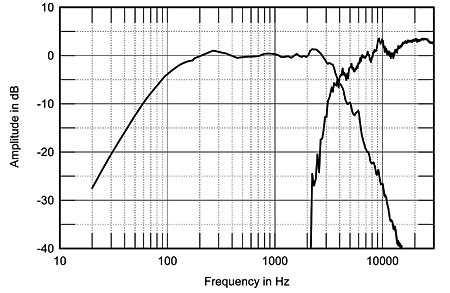

To examine the Modulus's anechoic response in a manner that minimizes interference-type features that will be too position-dependent to have any serious subjective effect, I average five responses across a ±15° lateral window. This is shown on the righthand side of fig.8. Notably smooth overall, it is broken only by a minimal notch at crossover and the rising trend in the high treble seen in fig.6. The lefthand side of fig.8 shows the nearfield response of both the Modulus woofer, plotted below 180Hz, and that of the servo-controlled Modulus Subwoofer. The two plots in the low bass show the difference in nearfield bass extension when the control unit is set to "22Hz" or to "35Hz." Note the restricted low-frequency extension of the Modulus when used on its own, –6dB at 74Hz referred to the level at 200Hz, though the sealed-box alignment does roll out at a relatively gentle 12dB/octave.

Fig.8 Infinity Modulus, anechoic response on tweeter axis at 50", averaged across 30° horizontal window and corrected for microphone response, with the nearfield response of the woofer below 180Hz, and the nearfield response of the Modulus subwoofer with the low-pass filter set to 22Hz and 35Hz and crossver set to 210Hz.

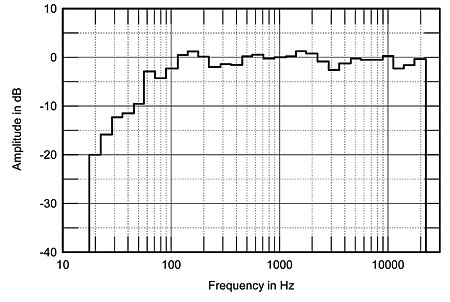

In-room and spatially averaged to remove the effect of low-frequency room resonances (fig.9), these quasi-anechoic responses translate to a broadly similar balance: restricted bass extension, a superbly smooth midrange, a definite lack of energy around crossover (correlating with the lack of immediacy to the speaker's sound), and a little too much energy in the top two octaves with the tweeter control at 12 o'clock.

Fig.9 Infinity Modulus, spatially averaged, 1/3-octave response in JA's listening room, tone control set to 12:00, no subwoofer.

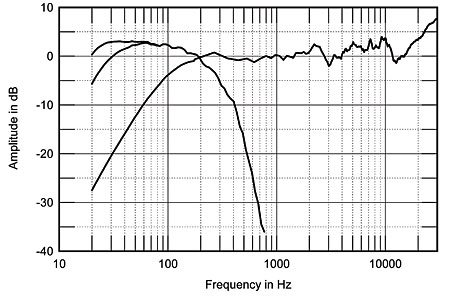

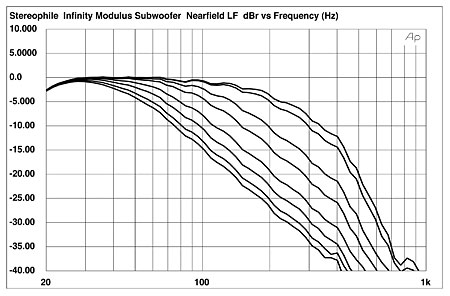

Finally, I examined the characteristics of the electronic control unit by measuring the subwoofer's nearfield response with the crossover frequency set to between 210Hz and 40Hz with the extension set to 22Hz (fig.10). This measured subwoofer performance, together with the continuous phase and level adjustment, will allow the maximum flexibility in integrating the subwoofer's output with that of both the Infinity satellites and loudspeakers from other manufacturers.—John Atkinson

Fig.10 Infinity Modulus subwoofer, nearfield response with low-pass filter set to 210Hz, 175Hz, 120Hz, 90Hz, 70Hz, 60Hz, and 50Hz.

Footnote 1: I've been asked why I use this "nonstandard" distance for MLSSA measurements, rather than 1m or 2m. The answer is that there are two mutually exclusive conditions at work with these quasi-anechoic measurements. Measuring at a 2m distance gives the optimum correlation with how the outputs from each drive-unit of a multiway design actually integrate at the listening position. However, the frequency resolution of FFT and TDS-type measurement systems is best when the microphone is very close to the loudspeaker because then you can get the largest time window between the initial arrival of the impulse and the first reflection from an adjacent boundary. (The anechoic frequency resolution is then proportional to that time window.) In a typical room with a 9–10' ceiling, a 48" distance gives a good compromise between the two needs when the loudspeaker is placed with its drive-units roughly midway between ceiling and floor, giving an anechoic time window of 4ms or so (which is why my cumulative spectral decay or waterfall plots also feature a time axis of some 4ms). Ideally, however, I would like a room with at least a 20' ceiling. Maybe I can persuade LA to excavate a cubical room, 20' to a side, in Stereophile's parking lot.—John Atkinson